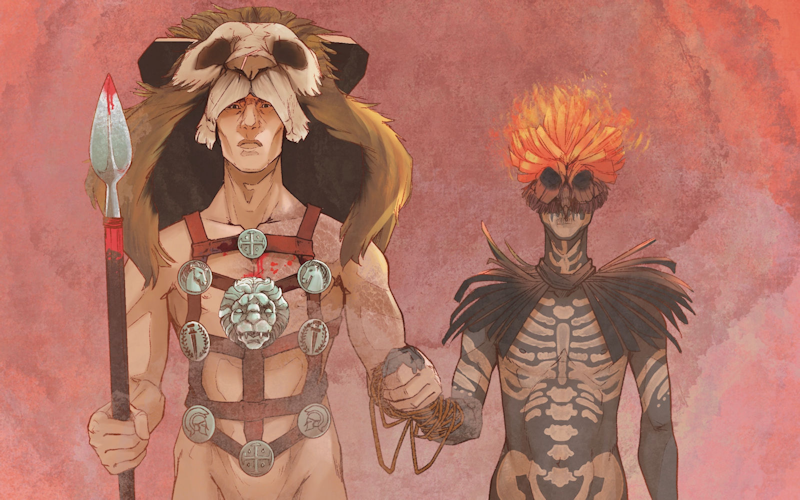

In this final conversation from Autumn’s last feast, Welletrix makes a deal with the loathsome Ancalite.

Warning: Web Draft! — Some content might be marked as sensitive. You can hide marked sensitive content or with the toggle in the formatting menu. If provided, alternative content will be displayed instead.

Warning Notes

Ongoing Edits

XXXV: The Colloquies: Minds Meeting

byMoonlight guides him five hundred steps from the kitchen to the barn. Unease quickens his heart as the worst thoughts plague him. Shadows dancing beneath the cowshed doors prove his hunch correct.

Loose hay strands litter the drive bay, where pungent tack and fresh lucerne begin clogging his nose. Warm air overhead brings his attention to the loft. There, the rangy druid sits under the tresses as coals smoldering in the floor pit cast an orange glow behind him. The serpent, Delphine, often spends cold nights up there, where the pit’s heat keeps the villa hives and honey stores from freezing.

Aedan the Ancalite—the prisoner, the cur, the monster—dangles a struggling rat over Delphine’s round snoot, his grasp on its tail firm. She bobs cautiously, her lipless maw gaping until her triangular head drops, unwilling to risk the rodent’s sharp teeth.

He smacks the helpless rat against the timber floor, silencing its squeals. He whips it over his head and slings the immobile thing across the loft. The serpent raises her thick upper body with it, falling upon her midnight snack with a thud.

Welle scolds, “She’s a hunter. Feeding her like that will make her lazy,”

Aedan’s black, lifeless eyes regard the blond Gaul standing at the ladder.

“We must talk, you and I,” says Welle in Greek.

Aedan says, “I forgive you for your unwillingness yesterday,”

Welle’s face twists with revulsion.

“Not about that, you perverted little cretin,” he snarls.

The druid rolls away from the loft’s edge, dismissing him. Unwilling to be ignored, Welle climbs the ladder, his bare legs thankful for the floor pit’s warmth.

Aedan remains on his side, unwilling to face the Gaul’s latest batch of bitching.

“Please.” Welle steps over Delphine, whose mouth surrounds the rat’s middle. He taps Aedan’s back with his foot. “Look at me, boy,”

Aedan yields, for this man, is too much like his mother.

“When I arrived here two years ago,” the Gaul pauses when Aedan retrieves the empty rat trap between them. “I need your attention,”

Aedan stares at him but with the trap in his lap.

“When I arrived here two years ago,” he stops again when the druid starts playing with the trap’s swinging door. Welle snatches it away, batting the druid’s hand away when he reaches for it.

“Give me that, and you’ll have my ears,” says Aedan in perfect Latin. “Slap me again, and I’ll beat your ass,”

Welle tosses the trap into the darkness below.

“I wish you would,” he barks, hand on his hip. “Raise a hand to me, boy, and you’ll lose it,”

Aedan grabs a chunk of honeycomb from the barrel top nearby.

“You were fluent in Latin when you arrived,” Welle accuses.

Dark eyes fix upon him without a word.

“Two years ago,” he says. “Fourteen families lived in the village. Last spring, when Lord Vitus didn’t return for the planting season, many Roman-born villagers moved south, leaving the plantation with a labor shortage.”

Aedan bites the top and spits a dry chunk of wax into the fire pit, making it sizzle.

“I told Lady Vita about a group of Veragrii widows living in the mountains north of the villa,” Welle continues. “These women had fled the tribal migration with their children during the attack on our camp at Bibracte. Lady Vita brought them to the village.”

Aedan gnaws upon its thickest portion, forcing honey from the narrow combs. Golden goo oozes onto his chin as his lips start smacking.

“After a time,” Welle thunders as the druid ceases his infernal lapping. “What Roman men remained married the Veragrii widows and their daughters. I know this because many came to me when it was time to join arms in matrimony.”

Welle spits on the hem of his tunica and, grabbing the man’s black curls, begins wiping that glistening chin. “They sought me out because my grandfather was a tribal leader and my mother a druidess.”

Thoughts of Ciniod haunt Aedan enough to break free of the Gaul’s motherly spit-bath. He crawls the water barrel and lowers his hands into the chilly water.

“Lady Vita ensured those couples got access to me,” says Welle, watching as the druid dunks his head into the barrel.

Aedan emerges quickly and shakes the water from his curls.

“Must you behave like a dog,” Welle scolds.

Aedan smirks without answering.

“Twenty families live in the village now,” Welle adds. “But only five are fully Roman,”

“Have they declared themselves a tribe?” asks Aedan.

“They did, over the summer,” Welle says.

The druid turns to him. “Why are you telling me all of this?”

“Last winter, too much snow led to empty traps, and the deer stayed on the warmer side of the mountain.” Welle moves closer, stepping over Delphine and the bulging lump in her throat. “The winter before that, constant rain brought rot to the grain supplies, and shortly before I arrived, no rains came in November.”

“You mentioned your first winter here in the kitchen,” says the druid.

“Yes,” Welle affirms. “No snow. And the bitter cold that came with it froze what little groundwater remained.”

Aedan leans over and looks into Welle’s troubled eyes. “He that presides over the dark half of the year ignores this tribe.”

“Karnunos presides over the winter wilds, coming into his own after the last leaf falls,” Welle tells him. “It is he who drives the wildlife into our hunting spaces. It is he who keeps the spores from spoiling our stores, and it is he who stops our well water from freezing,”

Aedan warms himself at the pit. “Is that your name for the great horned one?”

“Yes,” he answers, adding: “An offering to Karnunos must be made.”

Concern taints the druid’s coldness. “Have there been no solstice offerings?”

“The last three bonfires fell to ruin before an actual offering could be made.” Welle tucks his hands into the long-sleeve holes in his tunica. “I was unable to oversee last year’s fire, and as chosen tribal leader, it’s my place to—”

“-Play the white fox?” asks the druid.

Welle is stunned until he realizes the nature of things.

“Why am I surprised?” he says. “Our dark ones are likely twins,”

“Which is the true horned prince, I wonder?”

“Karnunos,” Welle declares, then tuts when the druid’s eyes roll. “Two-legged life didn’t begin on that island of yours, Ancalite. Your ancestors got there by fleeing the same mountain-eating ice as ours,”

The druid concedes with that side-smile of his.

“Ritual is timeless and the appetites of Gods everlasting,” says Aedan. “If your horned one is anything like ours, appeasing him after so many winters of discontent will take more than burning wicker and lamb’s blood,”

“The year I came here,” Welle tells him. “The fires collapsed, even though they built a sturdy effigy,”

“They could’ve burned a deeply rooted tree, and his wrath would’ve felled it.” Aedan grins. “You, need a druid,”

“Stop smirking.” Welle points, “Including you wasn’t my idea,”

“The great horned one begins his watch when the last leaf falls.” Aedan warms his fingers close to the coals. “Your solstice fires draw him in, but he won’t come alone.”

Welle comes alongside him. “What does that mean?”

“The other gods watch and feel in silence,” says the druid. “As they’ve been doing while Rome marches across their lands and scatters their flocks,”

Welle hardens. “These people fought tooth and nail against Rome,”

“Yes, but those in the village live well enough these days. Meanwhile, their cousins face slaughter at the hands of Caesar.” Aedan offers a reassuring hand. “But ritual can negotiate such truths,”

“No, I don’t like that.” Welle slinks away. “Physicality isn’t in my nature,”

Aedan stares at him.

“Besides,” adds the Gaul. “You were handling a rat as I arrived,”

“The problem is,” says Aedan, gazing momentarily at the barrel where he washed his hands. “Members of this tribe aren’t the only ones being judged,”

Welle’s eyes widen. “The gods see me as a traitor?”

“Not even I am immune from judgment. Not all of us are the same in the eyes of the gods.” Aedan’s bare foot finds the bulge in Delphine’s middle and begins rolling the hissing serpent from side to side. “Celts are sheep grazing in the fields. Nobles and druids are the shepherds, herding this flock with fear while keeping them safe.”

“There’s no other way then,” Welle murmurs before looking him in the eyes. “This year’s fire must come with…I can’t even say it,”

Aedan loathes the Gaul’s apprehension—no wonder Rome conquered his Alpine tribe so quickly.

“On my island,” he says. “It’s always a coward that best appeases the horned one’s sweet tooth,”

Welle nods, “It is the same with Karnunos,”

“Have you such a man?” he asks, bloodlust tingling.

“During the attack on our camp at Bibracte,” he says, nodding. “Lord Skipio gathered the women and children and ordered them to flee across the river before his infantry arrived.”

Aedan moves closer to the taller noble.

“Among those fleeing with them was a merchant who’d worked for my father.” Welle recounts that day with a heavy heart. “He’d stripped one of the dead women and donned her clothes. So, I told a horseman—”

“The battle-king’s son?”

Welle stares at him. “Planus isn’t Caesar’s son. He’s the son of Caesar’s aunt. And yes, I told him that a wealthy man had escaped them by crossing the river with the women and children,”

Aedan grins. “My bride must’ve been furious,”

“Lord Skipio,” Welle corrects him before tempering his voice, “and his men found the women in a cave, huddling with fear. Two of them were dead after trying to stop the bastard from taking their daughters. He planned to sell the children for passage through the mountains.”

The druid’s face is slack, no doubt fantasizing about Lord Skipio’s violence.

“They caught up with him and the children,” he continues. “Lord Planus returned with the girls, while Lord—”

“-those mothers?” Aedan interrupts. “The widows brought to the village,”

“Yes,” he replies. “They shed no tears upon learning that Lord Skipio had castrated the merchant,”

“Is this gelding nearby?” Bliss lightens those black orbs. “A coward is a beggar’s ration, but an emasculated coward is a hearty feast,”

“He appeared among the harvest slaves.” Welle ignores the man’s glee. “I failed to notice him. Lord Skipio didn’t see him either. A woman spotted him and told her husband. The men spirited him away from the slavers,”

“The bloody scene everyone thought was a bear attack,” Aedan muses.

“What am I thinking?” Welle paces around the pit. “I cannot master this ceremony,”

“You are the winter fox no one sees,” says the druid. “But the horned one must smell,”

“Fine.” Welle starts down the ladder. “I will inform Galbi that we will take part together,”

“The dwarf woman?” asks Aedan.

Welle scowls up at him. “Dwarf is not a word we use in this part of the world, druid,”

“I partake on one condition,” he says then. “The children must know why the coward dies,”

“Absolutely not,” Welle barks. “Human sacrifice in these modern times is bad enough, but I won’t have children—”

“The coward will die.” Aedan stares into him, face stone and voice steely. “And the children will know why.”

Fear seeps into Welle’s bones as the druid flips into a handstand before tipping over and landing before him in the drive bay.

“You know the horned one’s cruelty,” says Aedan. “A fallen man’s guilt will fill his belly, but the children’s terror will clear the aftertaste of their parent’s comfortable life.”

Welle sighs his forfeit. “The offering must be too drunk to know his surroundings. I don’t want the children to see that bastard intreating for his life,”

“Noble and druid must also show their unworthiness,” he says. “We’re the worst two men for this, and the Gods know it. We must show them that we know it,”

“Go before the Gods with our complacency exposed.” Welle thinks aloud before confronting the druid. “How do we do that?”

**

Oil light from a hanging iron lamp casts ghostly shapes upon the walls. Bearskin drapes to conceal the lakeside porch trap the bergamot scent of his Roman bride.

The enormous woven rug shelters their footsteps as they venture deeper.

“This room is off limits,” Welle whispers, grabbing his arm.

Aedan regards the Gallic nobleman with a sneer and thinks again of the bitch that bore him. “What we need is in this room, so stop being a little cunt.”

Pale blue eyes stab at him over the candle’s flame.

Aedan walks ahead, passing a ceremonial altar flanked by two iron cross stands. The first wears his bride’s battle armor, and the other holds that infamous headdress.

Welle gives light to the bureau lamp, bringing Aedan face to face with the lion’s mane. He scratches into the mane’s fur, now free of blood yet heavy with the scent of spicy hops.

“Lord Skipio had it cleaned,” the Gaul mumbles. “Took the man four days,”

Aedan moves away, stopping at a two-door cabinet along the shortest wall. Beside it sits a shorter bureau with four pull-out drawers. On his knees, he tugs at the bottom drawer.

“Get out of there,” snaps Welle.

Aedan rummages through too many familiars and finds the phalera vest and its many medallions. He brings out one with a sword and laurels etched upon it.

“He got this for defeating me and my bitches after we trapped one of their battle king’s foraging parties.” Another medal details a combed helmet. “This one is for driving the tribes from the Tamesa.” Another of the sword. “They gave this one to his father for killing mine. Then he got it for defeating me.”

It takes both hands to retrieve the largest, a molding of a lion’s face.

“This beauty is for slaughtering nearly every male druid in the river valley.” Aedan kisses it. “He also raped them, but there’s no medal for that,”

“Who told you Lord Skipio did these things?” asks Welle.

“I watched him from the trees,” Aedan whispers. “Every punch and thrust,”

Welle tuts. “I bet you cleared your cock’s throat while watching, didn’t you?”

Aedan grins, taking up another medal, one adorned with a cross. “I don’t what they gave him this one for,”

Welle wrenches it from him, bringing him to his feet.

“What did you do, Welletrix?

“That’s between me and the Gods, boy,” says the Gaul. “And you’re right. Wearing this will remind them that I am well aware of what I did and how I would do it again,”

Aedan gives the Gaul room as he begins setting everything back to rights. Through the fire’s flicker, a dark line along the wall catches his eye. Pressing it shows a panel door. He slides it right, revealing the darkest and tiniest space.

“A tomb for sleeping,” he says, entering the small room and finding its bed.

“Get out of there,” Welle whispers.

“You think Poppa Vitus brought his daughter in here?”

“That’s nasty gossip,” Welle’s tall figure soaks up the doorway’s light, “and you will not repeat it,”

“Does my bride bring women in here?”

“Lord Skipio doesn’t entertain women.” Welle folds his arms over his chest. “You of all people should know that much,”

“Then, I guess,” Aedan bounces where he sits. “I do belong in here,”

“You forget your place, boy.” Welle leans over him, candle in hand. “Just because you’re not sweating under a Roman boot doesn’t mean you aren’t enslaved. This villa is beautiful, but never forget, it is still a cage.”