Tempers flare when Aedan confronts his uncle during a meeting with tribal leader Cassibelanus.

Warning Notes

Violent Flirtation, CNC Kink

IV – The Arrival

byHaze shrouds a sea that blazes silver beneath the midday sun. Silhouettes appear on the horizon, five, then ten, until there are too many ships to count.

Tribal leaders who fled the mainland arrived on their island, recounting Prince Mandubracius and his pact with the Roman battle king, Kaiser. Fresh from the fight, they spoke of warlord Dumnorix ambushing the Romans with a concealed fleet. Alas, it’s now clear that Dumnorix is as dead as his fleet.

The brutish driver grunts. Stocky, with brawn outstripping brain, he shadows Begat, a gnarled crone who does enough thinking for them both.

“Ships can’t crawl over land,” she says, as if it’s ancient wisdom.

“What battle king drags ships over land?” Aedan eyes the fleas in her greasy hair. “Those ships will beach and shit blood-mad soldiers who’ll crawl over anything.”

The driver, eyes wide as he sees what they see, whispers, “Look at how many.” He suddenly turns and sprints for their flat-top cart, climbing awkwardly onto the driver’s bench and rousing both horses with panicked jerks of the reins.

Begat watches his frantic movements and begins scratching her ass. “That one will die first, I reckon,”

“One of many to greet Dumnorix before we do,” adds Aedan.

Eyes meet, and laughter fills the space between them.

“You’re a strange one, Owl King.” Her breath reeks of shellfish and mint. “The last one standing is always a strange one.”

“Why is that?” he asks after her.

“Gods have use for the strange ones,” she tells him.

The ride back provides little respite from the heat.

Aedan, struggling to keep his father’s robe on his bony shoulders, balances carefully as he stands atop the cart’s two horses, each foot planted on a horse’s back. The driver, glancing up, gawks at the druid’s exposed ass, uncertain whether to be curious or disgusted.

Most men don’t mind Aedan’s gaunt body after tasting his hole. It’s his soul they find unpalatable.

As the hilltop fort comes into view, the horses begin to breathe shallowly and charge toward the plank gate. When they near the entrance, the tall double doors swing open, allowing the cart to pass through before the guards hastily close them. Recognizing their surroundings, the horses slow to a trot.

Begat jumps off the flatbed and disappears into the shadows. Aedan backflips to the ground and cartwheels past unfamiliar warriors. Their swords catch the sunlight as he adjusts his robe, then heads for the largest roundhouse.

Inside, his mother quietly whispers to her brother, Taran, the druid leader of this settlement. The gaunt man draws plans in the sand while his sister reacts with childish enthusiasm. Disliking them both, Aedan announces Rome’s arrival as the driver enters; truth is a wicked stew, and Aedan enjoys serving it with too much salt.

“More ships than fish in the sea,” the driver says.

“Seven hundred ninety-three fly Roman colors.” One swift hop puts Aedan atop the table’s edge. He curls his toes around its hedging. “Three of them fly Treberoi colors.”

Ciniod starts. “Indutiomarus sails with Rome?”

Before he can answer his mother, Cassibelanus drifts in like a bad smell.

“Cingetorix rules the Treberoi now,” the warlord announces. His thin lips curl under a thick-brown pelmet, and his clean-shaven jaw contrasts with a hairless head—the man’s only attractive trait.

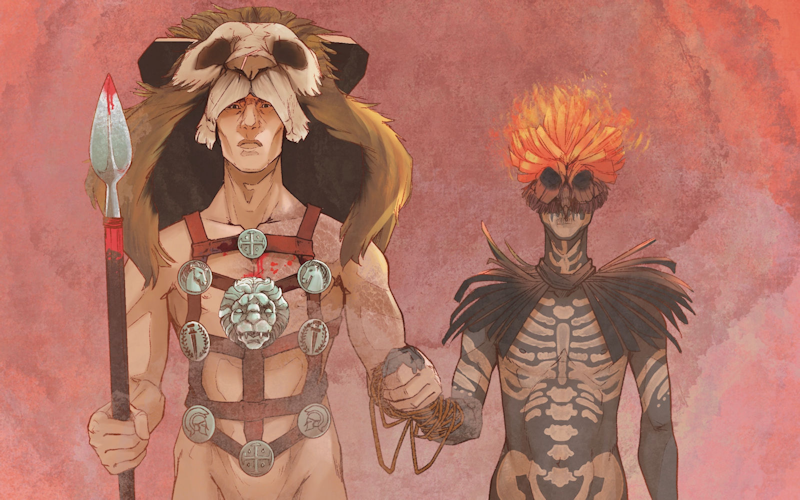

Aedan tolerates hulking Cassibelanus because the warlord always brings an entourage of foul-tempered warriors. Today, a sturdy redhead with a pale, freckled chest keeps glancing at Aedan, and when Aedan meets his gaze, the manlet turns shy, ducking his eyes like a boy just weaned from his mother’s tit.

“If Kaiser is here,” Taran proclaims. “Then Dumnorix is dead.”

The redhead whispers, “Why would Cingetorix fight with Rome?”

“Their families are under the Roman knife.” Aedan studies the manlet’s shapely bicep. “If they flee or revolt, their kin die.”

“Out little hoot-hoot is now a man.” Cassibelanus slaps Aedan’s back. “Perched up here like an owl. Bet you barely weigh as much.”

“This is the Owl?” the redhead asks.

“Kelr, fetch your mother,” Cassibelanus orders, sweeping Ciniod into his arms. “Chinny, you look well for a widow!”

Mother bares her blackened teeth and titters like a girl who has never bled. “Put me down, you fool!”

“My words are true even if foolish.” Cassibelanus sets her down and speaks in an affectionate tone. “You’re still beautiful, Chinny.”

Aedan retches loudly, startling Taran and the warriors.

“Enough of that,” his mother snarls, familiar with his antics.

“How can you carouse,” Aedan accuses with little emotion, “while my father remains undigested by the Gods?”

Ciniod glares at her son, her jaw tight and eyes burning, until the warlord steps into place between them. “We’ve bigger concerns,” he says, voice heavy with restraint.

“Nearly eight hundred concerns land as we speak,” says Aedan.

The warlord turns thoughtful, and a moment passes.

Aedan swears he can smell roasting meat coming from inside the man’s skull.

“Do you remember King Imanuentius’s cattle?”

The warlord meets his gaze.

“Before you killed him, he had six hundred cattle. Eight hundred is more than that.”

The warlord’s skin turns bumpy like that of a plucked goose.

“Taran,” comes the flighty voice of Avalin the Catuwellauni.

The sixth child and only daughter of the man who called Cassibelanus his heir, she floats in like a butterfly and embraces the lanky Taran. She then sings Aedan’s name and smothers him with kisses before tousling his curls.

“You’ve become a man, just like my Kelr.” She plants a final kiss on his cheek that he doesn’t wipe away.

Childless for most of her days, the Gods awarded Avalin a son once her bleeding grew irregular. Robust and perfumed, the honey-haired Avalin mothers every child, no matter their nature. If the Romans brought children, she will love them as her own.

“Is it true? Have the wolves returned?” Bright brown eyes drift from Taran to his sister. “Chinny, remember the first time we saw them? How we stood with our men and fathers on the cliffs?”

Mother forces a subservient smile, her lips trembling and eyes averted, her nature unfit for interaction with pleasant people. But interact she must, for Avalin commands many, relying on Cassibelanus, a man she has raised since he was a pup, to keep them in line.

“Your boy Kelr gets his first battle,” Ciniod says, faking excitement.

“We’ll set out before sunrise and attack their beachhead,” says Taran, intent on catching the enemy off guard before they can organize.

“Is that wise?” Cassibelanus asks.

“They won’t wait for you,” Aedan says. “They’ll march by night and find us.”

Taran shakes his head, “They don’t know this land.”

“It’s not their first visit,” says Aedan.

“I’m aware. I’ve faced Rome,” Taran reminds him. “On and off this island.”

“You faced Rome,” Aedan says. “And lost your face.”

Avalin steps behind Cassibelanus, who grins at their exchange.

“You would have me send fighters in the night?” Taran goads. “Their torches, targets in the trees?”

“Send the night hunters,” Aedan says. “Set traps in the widest woods.”

“Wouldn’t they use the trees as cover?” Ciniod asks.

“No,” says Cassibelanus. “Showing their numbers is strategic.”

“They’re disciplined,” Aedan adds. “March four by four on roads, three by three on natural paths.”

Suspicious eyes regard him.

“My father’s letters found me well enough,” he tells the room, then confronts Taran. “Your frontal assaults failed on the continent, and they’ll fail here.”

“I know this land,” Taran tempers his rage.

“Plan a contingency for when your beach attack fails,” Aedan says. “That is all I ask.”

“Fair request,” Cassibelanus says. “Lead a small party to intercept scouts.”

Taran nods. “Or better, fortify a nearby river.” He draws a circle in the sand around a serpentine line of dull blue thread. “We’ll gather at the Avona.”

“It’s too close,” Aedan says.

Taran tuts, earning a gentle pat on the hand from Ciniod.

“I was thinking farther north,” says Cassibelanus.

Taran shakes his head. “They’ll not cross the Avona.”

“Oh, but they will,” Aedan says. “And our dead will be their bridge.”

Avalin gasps. “Is that what you saw at the ceremony?”

“He saw nothing,” Taran says. “Bloodlust clouded any divination.”

Aedan stares at him, eyes blazing with silent accusation.

“Half our force stays east of the wood,” Taran decides. “If they cross the Stour, we fight on the Avona’s grasslands, here.”

“They’re strongest in open fields,” Aedan says.

Taran taunts, “Faced many Romans, have you?”

“As if that matters since you’ve done so and learned nothing.” Aedan relays his thoughts without emotion. “They’ve bested you time and again in free-range skirmishes, and here you are, humping the same leg you did on the continent, like an addle-brained dog.”

Cassibelanus tilts his bulk over the table, putting himself between a taciturn Aedan and the enraged Taran.

“What do you suggest, Owl?”

“He’s not Fintan’s successor,” Taran snaps.

“If not him, then who?” Ciniod whispers, quieting him.

Aedan says, “Send an emissary to open talks.”

“Invite them for mutton?” Cassibelanus jokes, sparking laughter.

“Avona is too close.” Aedan jabs a finger into the sand where the eastern grasslands run and draws a line to the stone marking their current location. “Kaiser’s horsemen will follow Taran’s retreat and burn this place to the ground.”

“Get out,” Taran cries. “I tolerated you because of your father, but no more.”

“I thought you were my father,” says Aedan.

Cassibelanus lowers his head, discomforted, while Ciniod aims her deadliest look at Aedan. A consummate peacemaker, Avalin steps to the emotionally wounded Taran and takes his big ears in her gentle hands.

“Aedan’s lost his father, and you’ve lost your…” She turns her sad eyes to Aedan. “Let’s hash this out further when your tempers have settled.”

Aedan retreats, with Taran’s sour regard tickling his back.

“The boy lacks his father’s temperament,” he hears his mother say. Cassibelanus counters, “Yet wields his father’s cunning.”

Outside, Aedan overhears the warlord’s intention to return north. Taran sounds hurt, but Cassibelanus insists they make their stand at the Tamesa, where he’ll have gathered the numbers needed to face Rome.

“We’re the first line of defense,” Taran’s voice wavers. “Are you of this thought as well?”

“I wish for no fight at all,” Avalin’s voice placates. “But if there’s to be a confrontation, we shall have it on our home shores at the Tamesa.”

Ciniod announces her intent to remain by Taran’s side.

Aedan finds her efforts to catch the warlord’s eye as pitiful as her loyalty to Taran. She hopes Cassibelanus might persuade her to go with him north, or at least provide her with some men for protection if she stays. The absence of the former tells her he isn’t ready to share his bed with her. His reluctance isn’t out of respect for her dead husband—it’s just her age: Cassibelanus prefers young, fresh women, not those whose passion requires grease.

“I saw you at the communal, Owl King.”

Kelr’s breath tickles his neck, and Aedan turns to find the manlet’s boyish face studying him.

“Mother’s right,” his thin lips twist. “Your eyes are darker than a raven’s beak.”

Aedan dips his tilted head closer.

“Can you see yourself in my dark eyes?”

“No,” says Kelr, pensive.

Without warning, Aedan shoves him, testing Kelr’s willingness to stand up for himself and see if he shares Aedan’s appetite for confrontation. Kelr keeps his footing, but his cheeks burn red as he grips Aedan’s narrow upper arms. He shoves Aedan to the ground, his mood a perfect mix of upset and irritation.

Aedan bites his lower lip, opens his legs, and bucks his hips. The manlet blinks in confusion, detaching with a protective hand at his gut. Bored with such indecision, the limber Aedan rolls backward to standing.

“When you’re ready to be a man, come find me.”

Kelr paces after him. “Why did you provoke a fight?”

“I hit you. You hit me.” Aedan climbs the water well to perch upon its bucket brace. “I fight you. You beat me. We fuck.”

“That’s insane,” Kelr says.

Aedan’s dark eyes gleam. “A blow to the face feels good.”

“Do you,” Kelr swallows hard, “do you like that?”

“I like that,” Aedan parrots, then softens.

They regard one another for several moments as passersby bustle about.

“Fine then,” says Kelr, unsure. “I can try what you want.”

Aedan backflips and lands on his feet.

“I need a man who does,” he says, walking away. “Not a boy who tries.”