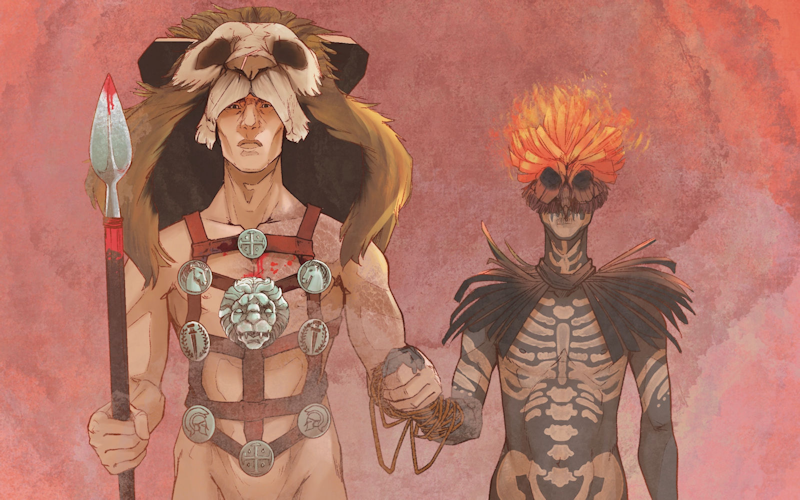

While out mapping the terrain with his father, Scipio encounters a lanky native with violent promise.

VIII – The Graticule

byFish and mud taint the wind, but there’s no sign of a river.

Charcoal in hand, Vitus Servius focuses on his sketch. The leather strap around his neck fastens to a flat board wedged beneath his belly, and upon it are many sheets of crisp vellum. Cletus, his steed, swats at flies with his tail and moves slow enough that Vitus’s skilled hand never strays.

Skipio, his son, snores upright on a horse whose name he never learns; he thinks only of his stolen mare, Luna.

Soon, they trade the hilly grasslands for flatter terrain.

“There’s woods ahead,” Vitus says, rousing his son. “Thicker trunks mean deep water.”

Skipio studies the dim woods and longs for home. Steady in his saddle, he conjures the lofty peaks around their plantation and the morning mists drifting over their villa’s glacial lake.

Slender trees obscure its depth and while birdsong abounds, something makes the horses hesitate. Vitus gives his beast a gentle kick, spurring him to enter. Leafy branches offer cool shade as Cletus follows a path only he senses. Skipio’s horse follows, hazelnuts cracking underhoof and releasing an aroma that tempers the mossy stench.

His father scans the leafy canopy, intent on finding this island’s version of a walnut tree. Pears and apples dominate their family crops, but all of Rome prizes the Servian walnut. His father had worked in the orchards before the Republic called him for his map-making skills. After serving with the legions as a young man, his father returned to the soil and started a family.

Skipio cares little about agriculture. Born with an illustrator’s hand, he found escape in swimming, and then horses, until Father insisted on sending him to the orchards. After months of scraping dirt from his nails, young Skipio had prayed to Minerva for liberty.

The goddess obliged when Skipio shed his boyish clothes for a manly tunic. Remus Plinius Castor, once a cavalryman, arrived at the Servian villa as a scholar recruiting students for his new school. Father, first uninterested, reconsidered his son’s enrollment only after Skipio chose drafting.

After five years honing his skills, Skipio was to return home—until Mars intervened.

At the start of his twentieth year, another of his father’s military friends, Julius Caesar, inherited the region. Caesar oversaw the building of a new colony, Novum Comum, and made it part of the Republic. Now a Roman citizen, Skipio quickly enlisted when the governor required all young provincial men to serve four years in the legion.

“You hear that?” Vitus asks.

The rushing water filters through the trees.

Vitus smiles, “Always trust a thirsty horse.”

Later, under the shade of whispering trees, they free the horses of their burdens. The beasts trudge to a ravine, muscles flexing as they step around hulking boulders and toward the curling water. Their hooves dent the soft riverbank before they plunge knee-deep, heads dipping to gulp at the stream.

A sweaty Vitus clambers after them, dropping to the ground to remove his boots. Skipio, perched on the boulders, watches his father strip, the man’s nakedness filling him with unease. Once lean, the mapmaker now thickens in unfortunate places; a harbinger of things to come. Skipio inherited his mother’s emerald eyes and full lips, but his physicality comes from his father. Neither man treasures the Servian curls, and that is why both shave their heads, even in winter.

While his father washes in the river, Skipio returns to the clearing to make camp. He pulls the leather tent from the saddlebag and unfolds it, fingers brushing its coarse canvas. Breathing in the loamy forest air, he hammers stakes into the earth, loneliness setting in as cicadas thrum in competition for a mate. If only he could find a lover among the trees.

Field spade in hand, Skipio digs into cool, damp soil, releasing a sour-sweet scent as he carves two shallow holes—one for their fire, the other for their toilet. His father returns to find him clearing sticks for kindling.

“Go wash up,” he says. “Scrub your feet. There’s nothing these blasted mosquitoes love more—”

“-than a foul foot,” says Skipio.

“I don’t need a mimic,” Vitus snaps, dusting their camp with rosemary and cumin, the only spices potent enough to repel this island’s ravenous breed of blood-sucking insect.

Skipio walks to the ravine and notices its flow moving steadily; there’s waterfall somewhere upstream and falls always have lagoons deep enough to lap. He leaves his horse behind and traverses the riverbank, crossing a downed tree to the other side. Anticipation quickens his heart, and his horse catches the feeling and follows along the opposite bank.

Soon, a faint whisper of rumbling water reveals a narrow fall tumbling over a rocky ridge. Its wide spherical pond beckons and Skipio plants his sword, sets his helmet on the hilt, and strips off his shin plates and tunic. Before removing his loincloth, he scans the trees, where birdsong drowns out his breathing.

Naked, he enters water murkier than the glacial ponds at home. Cold seizes his thighs and tightens his balls, but he marches on before losing nerve.

The roar of the falls softens as water floods his ears. Skipio swims, surfacing every fifth stroke for air. Near the far bank, he pivots and returns. Five times across, then five more. His heart drums within his chest as he rolls over, arms spread, back rigid as if crucified. With his legs fused, he sweeps his arms beneath the surface, gliding backwards as the air cools his chest and face. Tree-framed skies seize his attention, holding it as he swims eight laps across and back.

Going under, his mind revisits Castor’s injuries; the man’s infirmity being the reason Skipio is on this mission. Vitus, the legion’s primary mapmaker, must redraw those maps lost in the recent raid, but charting the valley’s key river, the Tamesa, is the real goal.

Deep within their enemy’s territory, this dangerous task requires a ranking decurion like Skipio. Tiring, he floats upright in a deep patch. Sun warms his scalp for the first time in weeks, and its rays cast color over the fall’s churning base.

Then, the birds go silent.

Skipio shoots upright and finds a native man watching him from the knickpoint.

Two small nipples mark a boyish chest, where the darkest hair peeks from underarm cleavages. Black curls drape thick brows but cannot hide the man’s large ears. The watcher displays no weapon other than an unpleasant face, but handsomeness isn’t vital so long the tongue holds talent.

The shallows provide a stable stone and Skipio steps onto it and stands to his waist, revealing his corded torso.

Cold eyes regard Skipio in curious measure.

The watcher peels his blue tartan pants down over his bony hips, exposing an inky thatch upon smooth obliques. Within this hair lies a thick cock root, and when deliberate hands take out a girthy shaft, Skipio cannot help but think of the deadly owl druid; are all the gangly men on this island so well-endowed?

As brothel courtesy dictates, Skipio falls back into the water playfully, bringing his hips to the surface to display his sizable manhood.

The watcher’s cold gaze never wavers, his hand twisting and pulling on thick flesh.

Such brazenness arouses Skipio, who enjoys the notion that these falls are now their brothel chamber. He lets slip a soft laugh before opening his mouth. He rests his tongue along his bottom lip, inviting the watcher to take aim.

A mischievous gleam clouds the watcher’s eyes as he works his flesh faster. His gaunt body tenses, and his breath shallows. Bars of sunlight invade, the heavens cruelly obscuring that glorious phallus as it spits. Then, his lips turn down, and the tartan britches return to their place.

Long fingers draw forth a thin knife, and with a jerk of its blade, the dare is made. Overcome by the challenge, Skipio steps onto a shale, emerging to his thighs and exposing his erection. A smile grows upon the watcher’s ugly face, then vanishes with a horse grunt. Dark eyes shift to the bank, where the horse stands with a sword, helmet, and clothes that reveal Skipio as Roman.

Skipio turns to explain, but the watcher is gone.

Misfortune tastes bitter. He slaps the water in anger, uncertain if the thick-cocked native can take a punch, or if his ass bleeds without oil. He emerges from the pond, glaring at the horse, which lowers its head in shame. Luna would never reveal herself—she had the courtesy to abandon her master during his lustful acts.

On the walk back to their camp, gnats swarm his face.

Suddenly, unfamiliar voices send him into the ground cover. Skipio controls his breathing despite his fear and through the weeds, he glimpses his father lying flat in the drop-off beneath their camp. Vitus fixes him with a raised hand while above, a robed woman and her brutes ransack their belongings.

The men devour their dried fish, while the woman, resolute, knots their barley ration pouch around her neck. A young man with red hair empties their saddlebags, then tosses Vitus’s spatha and armor onto a cache of loot. The woman untethers the horse, Cletus, and slaps him, sending him darting into the trees. Without warning, Skipio’s foolish beast bolts after him, drawing the red head nearer to Skipio’s hiding place. A true fire-crotch, the native hesitates, scanning the trees but missing Skipio, hidden in the brush.

These ruffians chatter in their strange tongue, and Skipio listens for any words akin to those of the Belgae.

“Where do you think they went?” asks the fire crotch.

“Down by the water, most like,” she tells him, then snaps, “Where you been?”

A flat voice responds. “Washing in the falls.”

Skipio raises his head for a peek and spots his bawdy watcher in the blue tartan pants. The watcher and the woman share an angular jawline, but her long black hair is straighter than his curly mop.

“Washing?” she smirks. “Or rubbing at yourself?”

Skipio knows enough of the Belgae tongue to understand her meaning, and the young man glares at her with contempt, as any son might a mother so crass.

“Get your poisons out, boy,” she says, smiling. “None of this lot’s going to smack you around to get that cock up.”

Skipio deciphers her words and risks another peek at his former watcher. Thoughts of slapping the slender native around and then sinking his teeth into those little ass cheeks begin rousing his flesh. When the woman commands her gang to torch the tents, Skipio looks to his father and spots him clutching their maps. He also notices the fire-starting kit dangling from his father’s tunic.

The lanky man withdraws from the group, inspecting the trees with a turning mind. The woman approaches and gently tugs his oversized ear.

“Did you see any Romans by the water?”

He responds to her in a loud voice, speaking Greek.

“I saw no one by the water.”

“Answer me proper,” she scolds. “You know I can’t speak that gibberish.”

The lanky man remains silent and does not join in destroying what is left of the camp. After a while, he joins the woman and her gang, leaving the smoldering tents behind.

They continue their scouting, and after several miles on foot, father and son hear their stomachs growl.

The mighty Tamesa appears as they crest the hill, twisting through the valley like a brown serpent. A wooden wall takes shape around a growing settlement, and near the river’s narrowest point, natives scuttle about like ants, each carrying out a given task. Burly types ferry grain, barley corn, and birch logs across the water. Round houses cluster along the reedy shore, with fur racks and tilled soil between them.

Skipio follows his father into some dense reeds and crouches with him as he turns his back on the river and begins sketching the eastern landscape.

“Those flat rafts” says Skipio. “They carry tin sheets wrapped in leather.”

“What does that tell you?” asks Vitus, charcoal moving over vellum.

“Their warlord readies for Rome,” Skipio says, then adds, “Their horse yard contains no chariots. They won’t be ready.”

Vitus whispers while sketching, never looking up. “West, there’s a settlement. An hour east, another. The closer we get, the quicker they’ll swarm.”

“We’ll be here within days,” he argues.

“Unless the Owl and those cursed raiders foil us first.” Vitus tosses the charcoal. “We must get clear of here. The natives have eyes everywhere.”

“You think they’ll find us?” Skipio asks, watching his father dip blackened fingers into the reedbed shallows for a clean.

“Only if we linger.” Vitus rolls up his illustration and ties it with a blade of long grass. “We’ll jog south to the coast and follow it back to the beachhead.”

Skipio balks. “That keeps us out another two days.”

“Yes,” says Vitus. “And we’ll live to see more—”

“-By avoiding the way we came?”

“Do not question me, Decurion.”

“Yes, Servius Legate.”

Once clear of the reeds, Vitus and his father jog across shifting ground. After several moments, however, his winded father slows down and begins walking briskly.

Farther from the river, their pace quickens and gulls appear in the cirrus.

Vitus talks of his cousin, a Comum orator sent to represent Comum in Rome. Each session of the Senate breeds more hostility toward Caesar, and resentment of his northern provincial cities. Talk of politics turns Skipio’s attention toward the horizon.

“Fear not,” says Vitus. “I’d never ask you to serve in Rome.”

“Why would I?” Skipio says. “Planus is more suited—”

“-He is of the Julii,” Vitus cuts him off. “Long before they came to the Larius, it was the Flavii who cleared the trees and we Servii who fed the quarry men.”

Skipio treads lightly around his father’s ambitions.

“There are far wealthier families among them than ours.”

“Despite our simple life, we are one of the wealthiest families.” Vitus stops walking. “Did you just refer to those in Comum as ‘them?’”

No further words come, silence drawing a fragile boundary Skipio will not cross.

Under the half-moon’s light, they traverse the coastal plain, which stretches endlessly save for the occasional cluster of boulders—some large enough for shelter. Father slumbers between two lofty rocks, while son, comfortable in the warm night wind, dozes atop the highest.

By morning, the wind settles and conversation returns; being Servii means never staying angry at those you love.

Gulls cavort overhead in the gray as Vitus talks of possible uprisings back on the continent. When the conversation returns to Comum, his father still makes no mention of Skipio’s mother or sister.

By midday, they find four Roman-made snare traps. The rabbits inside, dead from struggle, were likely left in the scout’s haste. Vitus sniffs each and takes only two.

They reach the coast as the sun melts into the distant surf. Near a silvery, petrified tree trunk, Vitus tosses his fire-starter pouch upon the ground, unceremoniously marking where they will make camp.

Skipio digs a hole for their fire with his gladius, as his horse fled with the shovel.

Vitus takes two flint stones from the pouch and sits cross-legged after his son drops a ball of patchy wool into the hole. They surround it with tiny bits of kindling before Vitus cracks the stones together. The stones finally spark and catch the wool, and he gently blows upon its sliver of smoke, growing the tiny flame.

Skipio gathers what sticks he can and stokes their growing fire, while his father tends to the first rabbit, cutting it about the neck so he can remove its fur with one mighty tug.

Vitus asks, “You recall those white cliffs we saw sailing in?”

“My Gallic boys say they’re made of bone,” says Skipio.

“These cliffs aren’t made of bone, they’re made of chalk,” Vitus tells him. “See that merchant bireme out there?”

Skipio squints at a dark patch on the horizon.

“She’s filled with slaves who’ve been picking away at it since we got here,” Vitus says.

Skipio carefully lays his shin plates over the crackling flames, the heat warming his fingers. “These cliffs, they’re larger than those at the end of the world.” He catches his father’s stare. “I know the Pillars of Heracles aren’t the world’s end, not anymore.”

“They never were,” says Vitus, handing him the skinned carcass.

“Where’s the salt?”

“Cletus ran off with the spice.” Vitus stares at him. “I can sweat on them, if you wish.”

Skipio takes the other rabbit from him, his face twisting.

“This sea here,” says Vitus, his voice laced with awe. “It’s not like our Mare Nostrum. It’s larger than the sky. Mark my words, Skipio, there’s more land beyond this island.”

The thought of unknown lands fills Skipio with dread; must Rome possess everything under the heavens? He tests the shin plates’ heat with spit before laying the red, white-streaked flesh upon them. Their tantalizing sizzle fuels his hunger, and buoyed by this comfort, Skipio finds the courage to ask after his sister.

“Vita stopped writing to me,” he says. “After I began serving the fort in Belacius.”

Vitus says nothing, his posture closing further.

Skipio presses, “Did she marry that—”

“We’re not talking about your sister.”

“Why?” Skipio demands. “What did she do?”

Vitus stares at the fire, offering no words.

Skipio asks, “Did Vita shame us in some way?”

“Your sister would never disgrace this family,” his father says coolly. “That’s the last words we’ll have on her.”

Skipio checks the meat, turning it when ready, so the other side can cook in the bubbling juices.

“Can you at least tell me if Mother has improved?”

“She’s taking care of herself,” says his father, melancholy. “As she’s always done.”

Mother fell ill shortly after their departure with Caesar, and his father actively avoids speaking of her inevitable fate, as is typical of a Servii. Such emotional distance is one coping strategy Skipio never emulates.

They make short work of the bland rabbit. While chewing, Skipio lets his mind wander, pretending he’s dining on a flavorful hare roasted in their villa kitchen by dear Nikonidas. Born to Greek parents and raised alongside Skipio in the villa, the amiable young man became the Servii cook after his father, the previous cook, passed away from illness.

“Is Niko still fat?” he asks, licking his fingers.

“Thick as Bacchus,” Vitus says, lifting the hem of his tunic to wipe his lips. “Your sister tells Planus he’s grown quite tall.”

“Is he still a mute?”

Vitus offers his displeasure. “His voice came when his mother lay dying. He’s not mute, Skipio, he merely doesn’t express himself like the rest of us.”

And with that, Skipio decides to confess.

“That native with the others at our camp,” he says, meeting his father’s gaze. “He saw me swimming.”

Vitus goes wide-eyed.

“It was careless, washing on your own,” he scolds.

“We saw each other,” Skipio says. “But he said he saw no one. And he answered her in Greek.”

“I wondered why he did that. He knew we were hiding nearby.” Vitus aims a guileful look at his son. “You saw each other, did you?”

Skipio grins, and his father sighs.

“Tell me you didn’t interfere with him?”

“If I had,” Skipio brags, “that bitch and her gang would’ve seen his bruises.”

Vitus heaps some judgment upon his son.

“You are nearing thirty years,” he scolds. “It’s one thing to never grow out of your attraction to men, but this carnal roughness—”

“-You have things you don’t discuss,” Skipio says, turning from him, “and I have mine.”

Vitus allows the moment to pass before speaking again, with consideration. “Planus never grew out of his taste for cock, either. Have you thought of making a match?”

Skipio raises his lip. “With Planus?”

“He’s your sort, isn’t he?”

“We’re the same sort, but not sorted for each other!”

Vitus sucks the rabbit from his teeth. “In that case, you’ll get a wife and ensure she knows nothing about whatever catamite you keep at our insula in Comum.”

“I would never fuck a boy,” Skipio declares, his stomach turning at the thought.

“Is that so?” his father challenges. “Well, you best choose a slave as your Ganymedes, since a slave will cause less insult to your bride and her family should they find out.”

“Is that truly fair to her?” Skipio wonders. “Is it fair to me?”

“Life isn’t fair.” Vitus stands, cracking the tension from his back. “We all make the best of this unfairness with private diversions.”

Skipio rises to kick dirt over their fire, his retort taken as his father stumbles to the earth.

A sudden head rush forces Skipio to his knees. His face collides with the ground, his feet and fingers fade; his arms and legs follow, vanishing into the ether as his heartbeat slows to a crawl.

Distant voices rise as his eyelids drop.

“I told you they would ride to the coast.”

“Yes, you did, my clever boy. Yes, you did.”