The ship goes from port to port, with oarsmen supervisor Gauda witnessing Servius Tribune and his Celtic captive test each other’s resolve.

Warning: Web Draft! — Some content might be marked as sensitive. You can hide marked sensitive content or with the toggle in the formatting menu. If provided, alternative content will be displayed instead.

Warning Notes

Ongoing Edits

XVII – The Month of Honey IV

byMalaca shows her Phoenician roots with an overabundance of stone and the absence of timber. Roman horses trot over her rocky jetty, each eager for a roomy stable with ample feed and fresher water.

Scipio comes ashore with Planus and Titus to heave their ship into dry-dock.

Much lighter without her cargo of men, horses, and grain, the Portuna Harena floats along a man-made canal. Her destination is a massive shed with concrete colonnades capped by a double-thatched roof.

Two hundred Romans strip down and saddle their shoulders with thick ropes. They drag the crewless vessel up the greasy slipway, and her hull rolls smoothly up two timber ramps coated with fat. Lugging her is the easy part. Keeping her slanted is the trick—her rudder must remain in the open space between the timber ramps.

After this backbreaking task, Scipio takes to the sea with the others, where local widows happily scrub them clean for a price.

Desperate for a hot soak and to poke his prisoner, he returns to the ship, where the legion’s physician intercepts him. The old Greek chastises him anew at finding his healing burns torn. There’s no blaming his violent games with the druid this time. The physician bans him from future dry-dock hauls.

Scipio, lounging on a treatment bench, dozes as the man dabs him with ointment.

Cold, dark water.

Mountains and mist, air thick with pine and rotting apples.

He hugs the driftwood as if lying atop Luna and rides the current with his head up and eyes open. The aqueduct, whose fiercer flows rival the most tempestuous river, carries him under a sky of wicker. Light filters through and casts tiny dots over his small body.

Mother’s voice tells him how the local women weave each screen to cap the elevated canals. Air must be allowed, and bats and birds kept out. There are missing screens on his journey, and father appears on the walk-over, his arms folded.

He floats to him, under him, and then onward…

Scipio wakes with a start.

A new moon brings the most distant stars to light. He curses himself for falling asleep. He drags his hand across his lips and coats his knuckles with something wet. It’s tangy and tastes nothing like ointment.

Furious, he plants an angry foot on the pebble-laden sand and finds the druid on a blanket beneath him. Luna lets out a soft snort, standing with her eyes shut and her tail twitching.

A strong autumn sun warms the chilly sea breeze.

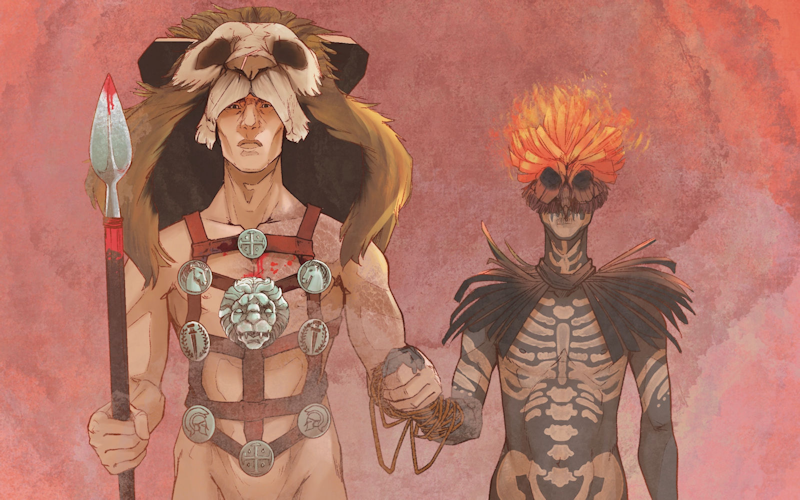

The sinew cord around the druid’s neck tethers him to his captor’s arm as they stroll the crowded narrows of Malaca. Boulders line the shore, many made flat by artisans so the local vendors can entertain with food.

Roman’s donning warm weather tunics sit upon rugs, each group awaiting someone to deliver their midday meal.

Scipio joins his friends amid a discussion.

“There’s our little runaway,” Planus declares. “After he and Luna disappeared, we thought him charging through Hispania on his way home by now,”

Scipio says nothing, he just pretends to admire the sea. The druid sits behind him, hugging his bony knees as Planus offers Scipio some water.

“Castor took off after him.” That elicits a bold stare from the druid.

“You sent Castor to hunt down my bride?” Scipio asks.

“No,” Titus laughs. “He took off without orders,”

The druid rolls his dark eyes and stretches his legs.

“You’re not truly taking this one home as a prisoner?” asks Titus.

“He will serve a life sentence for what he did to my father,” Scipio says.

“Yes,” Titus says. “But to call him your bride,”

“A life sentence,” says Planus. “If that’s not matrimony, I don’t know what is,”

“Worry less about my domestic affairs,” Scipio tells him. “And more about yours,”

“You hear that, Titus,” Planus teases. “You best get an affair of your own,”

“My mother has already arranged a bride,” Titus says. “One that will tie our family to the Ursii,”

Scipio grins. “Which sister?”

“Actus won’t tell him,” Planus laughs.

“I pray it’s the fat one,” Titus sighs. “Her beauty is timeless,”

“As is she,” says Planus. “Her first marriage took place the year Actus was born,”

“Age is a number,” Titus defends. “And at hers, I’ll never be burdened with children,”

Suddenly, a local appears with a steaming tray.

The bearded man sets a metal disk in the center of them, then removes the upturned bowl on top of it, letting out a puff of aromatic steam. Boiled eggs, their whites sculpted to resemble seashells, surround a thick tuna square covered with dark glossy sauce. Arugula peeks out from beneath the fish, each leaf a deeper green than the pickled cucumbers in tiny bowls alongside.

Scipio pulls a spoon from his tunic belt and uses its pointy end to dust off any chopped bits of hard-boiled egg from his portion.

“Eggs are good for you,” says Titus. “Especially at sea,”

“I want nothing to do with them when cooked this way.” Scipio carves a bit of tuna out with his spoon. “And nothing to do with you after you’ve eaten them cooked this way,”

“Your hardened egg gas, Titus, fuels nightmares,” Planus agrees. “I pity anyone with an open flame near your hole tonight.”

The tuna is tangy, salty, and good going down. Its sauce tastes of pepper, onion, honey, and vinegar, with hints of lovage and mint.

Actus joins their meal, spoon out before his ass hits the rocks.

“You were supposed to watch him,” Scipio scolds.

“I did watch him,” says Actus, sparing the druid a glance. “I followed him and Luna right to you,”

“Was I asleep?” Scipio asked.

“Yes,” Actus says, spoon in his mouth.

“How now,” Planus grins. “At least our Actus waited until your prisoner fell asleep before fucking off to places best not mentioned.”

Scipio levels his gaze. “What did he do before he slept?”

Actus stops chewing, unwilling to answer.

“Indeed,” Titus scolds, unaware of their understanding. “What if he cut our Scipio’s throat after you left?”

Actus swallows. “He has no blade,”

“Oh, he has a sword,” Scipio says.

The druid smiles behind his knees.

“Does that thing speak Latin?” Titus wonders.

“One wonders.” Planus spoons some tuna into his empty cucumber bowl and sets it near the druid before speaking his language. “You must be hungry,”

“Go on then,” Titus presses. “Eat, it’s a fish,”

“He comes from an island,” Planus reminds. “He’s well aware of fish,”

“I doubt he’s even human,” Actus says, shell-shaped egg in hand.

Scipio smirks. “His hole feels human enough to me,”

“Must you be profane?” Planus asks.

“I, too, wonder if the bitch understands Latin,” says Scipio.

“Given that glare,” Planus nods at the druid. “I think he understands the word bitch in any language,”

“Tell me, Ay-dawn,” Scipio says in Greek. “Do you understand Latin?”

The druid meets his captor’s stare and, without warning, spits.

Scipio wipes it from his nose and cheek, then backhands him, stinging his knuckles.

Blood wets the druid’s thick bottom lip until his tongue laps it away.

“That’s for the mess you made on my face last night,” Scipio declares.

The druid hocks more spit onto the tuna in its little bowl.

Scipio retrieves the bowl and tips the spittle-covered fish into his mouth, chewing with his green eyes set upon the druid’s.

Planus observes their exchange in horror. “You two need Salus,”

The prisoner’s behavior improves on the sail to Carthago Novum, but it is not until they pass Dianium that Gauda realizes he’s been listening and learning. In time with the drums, Gauda’s lessons fill the waking hours and are the druid’s only sustenance besides water.

They sail many nights before arriving to dry out in Tarraco.

It is the first port on their journey that feels Roman—colorful walls, intricate columns, vibrant tunics, and the blessed mutterings of Latin. Due to Gauda’s lessons, the druid understands most of what he hears while led on his leash through the city, yet his nights left aboard ship prove lonely.

His captor, young Servius the Tribune, forgoes visiting below decks. He communes daily with his most trusted, and Gauda hears whispers about reestablishing Novum Comum in the name of Caesar. Arguments occasionally prevail, but all eventually align with the Tribune’s plan.

Gauda’s eavesdropping brings trepidation—should strife break out between the Senate and Caesar, his new class of oarsmen will indeed be enlisted to fight.

Weeks pass, and the druid weakens from hunger. Still, he refuses anything brought to him by a concerned Planus, who notices the Celt drinks water offered by Gauda.

Planus is a handsome Roman with flirtatious eyes and a witty tongue. He offers the well-dressed supervisor of the oars a deal: get the prisoner to eat something and earn some extra coin for days in port. Gauda considers it, of course, if allowed to spend some of that extra coin on dining with Planus.

Servius the Tribune is unaware of their arrangement, and on the eve of their arrival at Massilia, he appears with bread and oysters. He threatens the druid: eat willingly or have the food chewed up by one of the rotted tooth rowers and forced down his throat.

The druid calls his bluff, knowing the Tribune won’t bother the oarsman.

Servius enters the cage and, after some ugly wrangling, forces the druid’s mouth open. He shovels oysters into it, clamping his jaw shut and pinching his nose until the druid has no choice but to swallow.

The Celt wrests free, but instead of kicking his captor like usual, he grabs the Tribune’s hefty manhood, jerking it violently until it’s fully erect.

Servius gives in and jams his member into the Celt’s mouth—warning him that if bitten, the druid dies. Yet even Gauda sees the Celt’s scheme for what it is when he chokes on it, bringing up the oysters and then laughing at the mess.

Furious, young Servius grabs the Celt’s head and forces it down, determined to make him eat his vomit until Gauda protests. He begs the Tribune to please allow him to clean it. His passion cooling, young Servius shoves the Celt aside and angrily returns to the upper decks.

Later that night, Gauda brings the Celt some bread and dried meat and politely asks him, in Greek, to please eat. When the Celt does, Gauda’s nerves settle.

The days pass, with Gauda bringing him antipasto meats from Planus. It’s peaceful for a time, until one day, Servius the Tribune appears clean-shaven and with his golden curls shorn. He drags his prisoner topside for a good wash.

The Celt’s grasp of Latin is nearly fluent, and he quietly countermands an order given to the ship’s steward to shave him bald. He asks the man with his strange blades to shorten his top and cut close almost everything behind his ears and on his nape.

Young Servius finds this pleasing since his captive resembles him from their first meeting. No longer weak from hunger, the Celt suddenly backflips to starboard and cartwheels into the sea. Servius dives after him not a second later, stroking over the choppy surf until he overtakes his prisoner. They struggle in the depths, but the larger man wins, as always.

Furious, he hauls the wayward Celt back and begins beating him on deck. The Celt counterattacks, and onlookers cheer him with every landed kick. Soon, his agile limbs fail to keep his captor at bay, and one punch to the head ends their fight.

Scipio finalizes all of their Comum plans on the overnight at Forum Iluii.

He wanders town with the others, finding little to interest him at a local boy brothel, not even Castor, who offers to share a man with him. He skulks back to the ship, eager to catch the druid sleeping, but instead hears the supervisor, Gauda, supping on wine, cheese, and meats with his prisoner.

“We shall speak Greek,” says Gauda, watching the druid make short work of the cappacola. “To answer your earlier question, we haul the ship ashore every other port because she’s wooden. Wood gets water-logged and must dry out after so many days to maintain her hull,”

Scipio listens at the ramp’s entry, confident the druid understands.

“Does she get a new painting of pitch?”

“Of course,” Gauda says. “I’ve answered your question, Aedan.”

“Now, you wish me to answer a question?”

“Yes,” Gauda says. “That’s how conversations work,”

Silence comes as the druid acquieses.

“How did you end up in such a predicament with our noble Tribune?”

“Noble?” huffs the Owl.

“I’ve heard his lust comes with a dose of violence,” says Gauda. “But from what I’ve witnessed these many weeks, you’re the sort to crave such violence,”

“There are others like me,” the druid says between bites. “I thought myself alone,”

“Not alone, no,” Gauda sounds amused. “So how is it that you two found each other?”

The druid speaks his truth—and Scipio’s.“I murdered his father. His father murdered my father.” The silence lasts a blink. “My mother murdered us all.”

“Where is your mother now?” asks Gauda.

“Dead,” says the druid with a burp. “She did right by me, though, as was her way, even when I toddled at her knees.”

“You’ve got the Tribune’s cord around your neck today.”

Scipio’s eyes fall to his arm; when did the bastard take it?

“It’s not his bind,” the druid explains. “My mother bound us in marriage with it before giving her life to the Gods,”

Gauda gasps. “You married your mother?”

“No,” the druid speaks with little emotion. “Your noble Tribune is my bride,”

Scipio balks in the shadows.

“One might say you’re the bride, Aedan,”

“Whatever I am, it’s temporary,” says the druid.

“I’m a bit too refined for that sort of man-woman construct,” Gauda confesses. “But as far as husbeasts go, you couldn’t ask for a better-looking man,”

“He’s beautiful,” the druid abandons his Greek. “Like thunder striking the sands,”

“Your Latin is much improved,” Gauda beams.

“I’ll not need it when I go home,” he says in Greek.

“When I was a boy, Rome destroyed my world.” Gauda finishes his wine. “I don’t remember the gods who failed to protect me, my parents, or my brothers.”

“We will prevail,” the druid declares. “Our tribes will outlive their Republic,”

“I prevail by surviving,” says Gauda. “I’m a Roman citizen and afforded the right to choose my destiny.”

The druid muses, “I suppose there’s a dignity in getting to choose where they bury you,”

“Someday, dear Owl,” laughs Gauda. “You will be a Roman citizen,”

“I’ll die first,” he tells him.

“You may become a father,” Gauda says, and the druid frowns. “Or a true bride. Either or, dear man, when it happens, you’ll understand that your name need not be Defeated.”

And to that, Scipio leaves without showing his face.