Lord Servius partakes in his first walnut harvest as family leader, a laborious affair made lively by the nimble Owl King.

Warning: Web Draft! — Some content might be marked as sensitive. You can hide marked sensitive content or with the toggle in the formatting menu. If provided, alternative content will be displayed instead.

Warning Notes

Ongoing Edits

XXIX: Nucum Messis

byLong before the human curse, a colossal vent erupted, flooding the vast icy landscape with its molten blood. The searing ooze cooled and, with time, became the blackest, most fertile soil. A cauldron valley is all that remains of Vulcan’s fiery child, its majestic crown now a half-moon stretch of peaks that cast shadows a mile wide.

Dawn’s first light creeps over the range, its gentle warmth felt throughout the plantation. Southern winds soon follow, catching the village procession on their descent, playfully whipping at tunics and blowing out trousers.

Excitement fills the air, particularly among the children, who bounce about the carts with an infectious energy. Among them, the elderly sit, their aching joints medicated with the traditional morning libations of herbal teas.

Brawny draughts pull them along, gravity an ally as the wind combs through their downy fetlocks. Each auburn beast, a pair to three carts, stands fifteen hands high, with thick haunches and hooves wider than a man’s head.

Behind them walk the other villagers, whose steady chatter calms their new master, Lucius Scipio Servius.

Responsibility weighs heavy on his brawny shoulders, and though walking in front, he’s careful not to outpace the expensive priestesses from Comum. Acolytes join their number, urban eyes wide with wonder at the towering mountains that flank his plantation.

Rows of pear trees line the service road, their gnarly limbs bare and winter leather blanketing their trunks. The trenches between them brim with water in anticipation of the coming cold, a helping hand their sister apple trees in the farther orchard can do without.

The draughts gain speed on even ground, beating the walkers to the valley’s edge, where imposing alps form a wall to the clouds. Green bushy canopies wave on their approach, and their pinnate leaves rustle on bobbing limbs heavy with verdant drupes.

Impatient children leap out of the carts before they come to a stop. Most eagerly await the walkers while the more spirited race out to them, demanding that they hurry.

A makeshift camp along the grove’s edge offers new faces in the form of Gallic slaves. All rise as the procession approaches, each man dressed for the chilly harvest day. Anxious looks dance between those villagers with children, their concern valid amidst so many strangers.

Prayers begin when the groups come together around the High Priestesses of Tutelina. First, she thanks the southern wind, Auster, for his timely arrival, then, after leading all in cheers to Tellus and Sol, a song is sung for Ceres-Liber.

Yes, the harvest gods are spoken of with their Gallic names, a consideration for those without Roman ancestors.

Afterward, the village foreman, Italus, and the village forewoman, Cassia, bestow everyone taking part with squirrel-pelt hats. The smallest are also awarded sticks, a token that allows them to serve in the ranks of Messor, the reaping god.

The bubbly harvesters file in behind the priestesses in an orderly procession. They follow in silent reverence, circling the grove until they reach a sliver of barren dirt where a quarried portion of the mountain meets the rows. Dense nets cover the grove bed, a sacred space where no one shall tread until the priestesses ensure every child’s fur cap is set and every adult receives a thumbprint of leaf ash between the eyes.

With the mountain at their backs, they form a line that stretches the length of the grove and then wait in anticipation of Lord Scipio’s commencement speech, a tradition passed down from Lord Vitus Servius.

Scipio Servius may resemble the noble Vitus, but he is not his father. Like the children struggling to retain their calm, this is also his first walnut harvest.

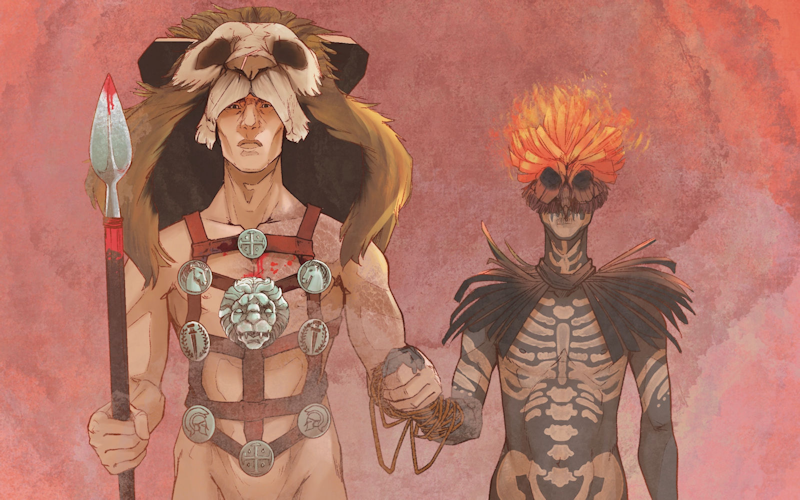

The muscular Servius appears on a hastily built timber deck. Alerus, a burly blacksmith, helps him steady the tall battle horn from Britannia, a towering instrument with a deltoid nose over a mouth lined with triangular teeth.

High on the hill where no one sees, Aedan Britannicus, the master’s druid prisoner, finds this use of the carnyx as a celebratory instrument heretical. His disdain grows as Servius steadies the ornate horn by its long neck and aligns his lush lips with the mouthpiece.

Cheers fill the air until the horn’s frightening howl brings silence. The sinewy druid huffs a laugh at their discomfort—the channel shark’s moan isn’t meant to commence festivities.

Once the horn ceases, however, the harvesters excitedly dash forward like dogs let loose to the reeds. The youthful and the lightweight clamor up the trees while the village educator, a wispy balding man they call Gratius, leads the littlest ones to knock free the low hangers with their sticks.

Branches shake violently, shedding drupes that split upon striking the ground. With a broom shovel, Servius joins those trailing behind the reapers; if a net becomes too full, he and his men push the overage to an emptier patch.

Laughter, babble, and the pattering of fallen stone fruit fill the air—a symphony that holds the druid’s attention until his stomach lets loose a growl.

As the late morning sun washes the grove in a warm glow, the harvesters, unaware of the feast preparations, reach the center.

Nikonidas Orobius, following in his father’s footsteps, leads the village cooks with a tenacious focus, stoking fire pits and chopping fresh goods under makeshift tents that rattle in the wind.

Nearby is Welletrix, a proud member of the Veragrii, who meticulously oversees those sharing his blood as they set up tables and lay rugs.

Across the grasslands comes Vita Servia, the Lady of the House, who gracefully commiserates with Comum’s visiting nobility, her pride in the plantation evident in every gesture.

The wily druid stealthily moves among them.

He idles up alongside Nikonidas, who stands with one hand on a brick of prosciutto and the other wielding the longest of narrow blades. With eerie skill, he shaves the white-coated meat, creating translucent ribbons that form a pile he shoves aside after a time.

Two youthful men hover over an enormous bowl of ripe red grapes. They roll each ball between their thumb and first finger, forcing the seeds out, and then pass the grapes onto the kitchen crones, Hostia and Vibia, and their arugula pile.

Wooden skewers in hand, the seasoned kitchen mavens thread their bounty, rotating grapes, prosciutto, and arugula. They set them upon cheese trays, each wet glob beckoning with creamy allure.

Unable to resist, Britannicus swipes a skewer from the tray, savoring its length before withdrawing it clean. His mouth makes short work of the fruits, meats, and greens, which come together exquisitely on his tongue. He reaches for another and finds the tray replaced by a giant bowl of dark greens sprinkled with chopped figs and nuts, the same pine morsels found in those cones in the villa peristyle.

Nikonidas takes a long grater in hand and rubs a pie slice of hard cheese over its pocked surface. A heavy dust of stinky flakes falls upon the greens as Hostia scrubs her hands in soapy brine. When he pauses from the grating, she digs into the bowl, tossing it all together.

With a disdainful sniff, the druid abandons them and follows his nose to a massive pig on a spit.

The villa morons, Caeso and Optus, tend to the trussed beast, taking turns with one spinning the rotisserie and the other basting its corpse with a concoction of olive oil, apple juice, wine, and pepper.

“Oh no you don’t, boy,” scolds Welletrix, slapping his fingers as they reach for some bubbling black skin on the snout. “This hog is for those working the harvest,”

Britannicus glowers up at the blond, until a cart of warm, fat rounds with crusty dark coats passes between them.

“You’re not getting any bread, either,” the Gaul decrees. “You want food? You work like everyone else.”

The druid turns his dark eyes to the grove before gracefully cartwheeling away.

Sol reaches its highest point, lording over the valley long after midday.

Servius and his men reach the end of the grove before retracing their steps. Back where they began, dozens of teens rush past, all armed with long willow branches. They whip at each other under the guise of seeking out missed drupes.

Many men chose their wives this way or were chosen without realizing it. This harvest courtship tradition catches the Servian master’s interest as he helps tie up the nets.

Suddenly, as if from nowhere, green balls rain down as the highest branches shake. A group of joyous girls races through the trees, a young man following close behind them.

“It’s him,” cries a girl. “It’s the Owl!”

“He’s so beautiful!”

“His skin is so pale,” yells another. “and his body so slender!”

“He’s not wearing a loincloth!”

“Did you see it?”

“It’s bigger than my baby brother’s arm!”

“They say Lord Skipio is just as big,” comes a young man’s voice.

Servius cannot believe his ears.

“Did you read the last installment from Pontius?”

The youthful voices fade.

“The Owl nearly drowned at sea until Lord Skipio…”

“I’d love for Lord Skipio to save me,” whines the young man, and the girls scream.

Anger burning his cheeks, Servius makes a mental note to have his old friend Titus Flavius track down the older brother of Virgil Pontius, and then burn every scroll of this ‘Lion et Owl’ they find.

Thoughts on how many readers the sordid tale accrues plague him as overhead leaves rustle violently and drop more drupes. Suddenly, through a bare spot, the druid appears, passing over them like a flying squirrel, naked ass visible under his long tartan smock.

Britannicus vaults from the last tree, landing upon the lush grass with a tumble before finding his feet. The scent of the earth fills his nostrils as he strolls to one of the draught horses and rubs clean his runny nose on the beast’s rump.

Once the nets are all tied, the men secure them to a large rope bound to a massive tree trunk on the grove’s center road. Servius emerges from the trees and gives a sharp, piercing whistle that sets the draughts into motion.

The beasts advance, dragging the thick tree trunk out of the grove, now heavy from all the attached nets. Their handlers lead them several yards to a stretch of pavement. As the mighty log crawls over the concrete, the workmen stall the horses and cut free the nets.

After the log gets dragged off, slaves rush in to untie the discarded nets, joined by Servius, a man no stranger to labor. Together, they shake free the torn drupes as workmen come in behind them and drop flat timber fence panels.

Boisterous women and children rush onto the boards and begin jumping. Farmhands lead oxen onto them next, in a parade that soon includes sheep and cows. With each cycle, the anticipation grows.

Finally, the panels get taken up, revealing a legion of greenish brown nuts amidst a sea of shredded green balls. Everyone swarms in, even Servius, plucking out the dewy nuts and tossing them over to the dirt path between them and the millrace stream.

This frenetic gathering is not just a race but a joyous celebration that the youth and children revel in with equal measure. Near the end of their riotous contest, new draughts arrive with the druid astride their wide backs.

His robe, a vibrant tapestry of autumn shades, matches the large leaves entwined in his diadem. His owl mask, crafted from walnut bark, is adorned with whimsical lines and circles designed to captivate the young and entertain the old.

The druid performs a stationery flip upon the horse’s backs as the pusher plow’s angled edge forces nuts into the millstream. The youngest cheer ecstatically, their infectious furor spreading to the priestesses, who holler and clap at the Celt’s acrobatic feats.

Even the frosty Welletrix admires the show, his glowing eyes accompanying a toothy smile. The Gallic slaves, their faces etched with fondness and the oldest among them nostalgic, also watch. Their pleasure isn’t lost on Servius, who marvels at their connection—no matter how many mountains, rivers, and channels divide these Gauls, their similar customs bind them.

The beasts clop to the stream’s end, where an undershot water wheel scoops up the floating nuts and drops them in a tailrace creek.

Children crowd the narrow waterway’s banks, following the bobbing nuts until they spill into a long trough. Here, with their practiced hands, the village men gather them with little stick nets before tossing them onto fresh carts.

Once the carts are full, Servius addresses his villagers and slaves, telling them a feast awaits on the eastern pasture. A cheer breaks out, and like a flock of birds, the hungry crowd migrates to the rug-covered grass, where wine barrels await alongside tables filled with food.

The cautious druid travels with the carts to a wide barn on the northern grasslands.

Large double doors open to a sunken floor where wood charcoal glows after an all-night burn. Lean iron trays cover the pit, each sheet an arm’s length above the embers so they’re warm but never hot.

Fieldmen disconnect the horses, then pull on ties that hitch the carts up at one end, dumping thousands of greenish nuts onto the trays. Slaves, with the longest push brooms the druid’s ever seen, meticulously spread the harvest evenly until no nut rests upon another.

Silvio, the plantation’s paunchy groundskeeper, instructs the newly arriving Servius on the next steps. He explains that the fresh nuts must warm until midnight. Then, the trays get thrust onto the barn’s stacked shelves, where they dry until the Ides.

The druid slips away unseen.

He finds the pasture mostly vacated except for a few generous villagers drunkenly breaking open another wine barrel for the slaves, who cannot return to their masters sober.

Bare, gnawed-upon skewers litter the empty salad bowls, and not one crumb of bread remains—the laboring cunts even gobbled the last ball of soft white cheese!

Head hung low, the druid skulks over to a village man sleeping in the grass, but before he can take out his cock and piss on him, Nikonidas enters his territorial bubble.

Broad cheeks dark from drink, his bright brown eyes twinkle before displaying a smile. In each hand is an apple, and he offers the reddish one to the druid.

Britannicus raises his mask. “What about Looir?”

The cook mulls it over before giving him the green one as well, and before the druid gives his thanks, the cook vanishes.

Twilight brings cooler air and a hint of the brightest stars. Back up the first road, crickets sing from the pear orchard while toads belch greetings from its watery canals. The trek grows steep, for unlike the western road, this service path doesn’t ribbon upon itself along the mesa.

The druid’s gaze falls upon the villa yard’s wall as the early darkness envelops him. He carries both apples but reconsiders visiting Looir—the mortared barn contains honey, though something named Delphine guards its grain and wine.

A tap on his shoulder promises the Greek, perhaps with more of something tasty, but turning around brings a hard fist to his head—a world-blackening goodnight kiss from Servius, his Roman bride.