Welletrix ruminates on how he came to live at Villa Servii.

Warning: Web Draft! — Some content might be marked as sensitive. You can hide marked sensitive content or with the toggle in the formatting menu. If provided, alternative content will be displayed instead.

XXXVIII: The Complicated Helvetican

byFirst light in the peristyle finds a child raking at pale sand, freeing cat shit and whatever else the feline gremlins bury for safekeeping.

The grand fountain churns softly, the villa’s groundsmen removing a sizable portion of its water after the first frost. Soon, they will drain it ahead of the first snow and fix an angled tarp over the open roof. Each accumulation, the groundsmen will cut the tarp’s sewn navel and drop snow into the fountain’s pool.

Villa Servii contains two hemispheres, with the Servian apartments taking up most of the lakeside. The portion bordering the hortus contains a triclinium and the toilets—not beside one another, mind you, but separated by two cubicula, one of which belongs to Welletrix the Veragros.

Part of his name comes from where his mother lost her maidenhead, and the other from being the Veragrii tribal leader’s bastard grandson. Welle begrudgingly abandons his tranquil room, marching through the portico hall and leaving his side of the villa for Lord Skipio’s apartments.

A thin oak door stands beside a wall niche shrine to Juturna, the deity responsible for keeping the villa fountains healthy. A burning candle floats within her little wooden offering bowl, where Niko puts well-polished stones every morning. Welle enters without knocking, certain Lord Skipio swims his laps in the frigid lake.

Things change when a dead man’s son takes over his private space. Decades-old crimson and gold become the palest blue with cottony blotches where the wall meets the ceiling. Clean charcoal lines form a dense forest where thick trunks and meshing branches offer more leaves than Welle can count.

This mural will take Lord Skipio at least a year to color, with him residing most days in Comum.

Welle fingers the medallion in his pocket and takes a knee. Trembling fingers graze the leatherbound trunk beside the man’s wardrobe, its silver bracket made by the same camp metalsmith who stamped a Helvetian cross into this medallion: two spears, one standing and the other lying across its center.

Lord Skipio no doubt earned it on the banks of the Saône. Hopelessness, fear, and dread; the names Welle gave to the Roman cavalry swarming down the hill and toward his grandfather’s baggage train. His stomach turns just touching the medallion, but before he can return it to its rightful place, the Servian heir enters.

“Lord Skipio.” He stands, noticing last night’s tunic. “Did you sleep in the baths?”

The strapping man passes him without asking why he’s there.

“I couldn’t fall asleep, not after last night.”

“If I may explain—”

“Explain what?” Skipio pulls the tunic over his head, displaying fresh bruises on his midsection and thighs. “My family is no stranger to your murderous rituals.”

“With all due respect,” Welle asserts. “We alpine tribes haven’t indulged in human sacrifice for generations.”

Skipio tosses the tunic, and Welle catches it.

“My words aren’t judgment. Rome is no stranger to such barbarity,” he says, then eyes the medallion in Welle’s grasp. “How many innocents did we murder at the Saône?”

Welle steps to the wardrobe.

“My mother was a druid,” he says, pulling out a pair of thick golden trousers with a fine, dark green stitch down the leg. “She didn’t grow up with ritualistic murder, and neither did I.”

Skipio sits on the room’s cushioned bench, while Welle kneels to align the trousers’ holes with his feet. “Tell me,” he asks. “How many of our villagers are Alpine Gauls?”

“Two families remain, one of them sent to Villa Servi the same day as me,” Welle says, pulling the trousers up and over Skipio’s muscular backside as he stands. “The rest departed for the northern mountains when your father didn’t return last year.”

Skipio shakes his head when Welle pulls out a green tunic.

“That one makes me itch.”

“It matches the pants,” says Welle.

“I don’t care,” Skipio declares. “We arrive in Comum after sunset, no one will notice if my top doesn’t match my bottom.”

“On the subject of your bottoms,” Welle says, frowning at the man’s choice in something black with long sleeves. “Will you be taking the druid with you?”

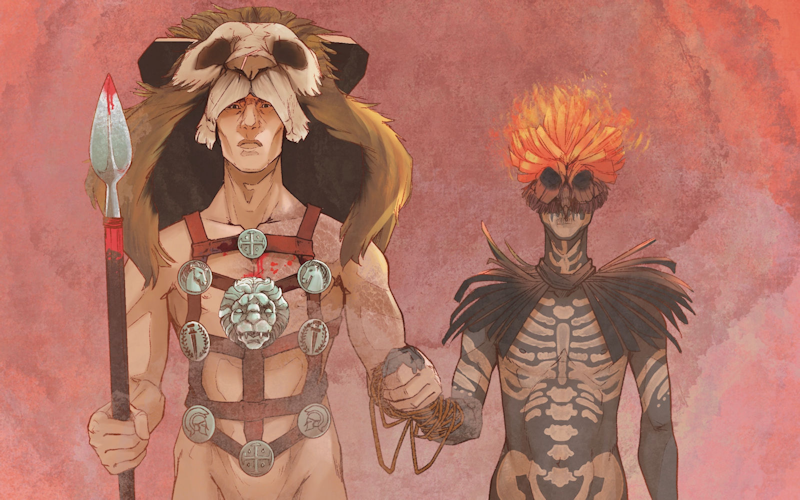

“No.” Skipio stands before his father’s long, standing mirror, his eyes finding Welle’s face in its foggy glass. “The Owl King murdered too many Lario-born men in Britannia. It’s easier for them to abide rumors of him living under their leader’s boot so long as he remains here, in the mountains.”

“Out of sight,” says Welle. “Not on the mind so much.”

“Exactly.” Skipio faces him. “So, our village consists mostly of Gallic war slaves?”

“Don’t worry.” Welle plucks up a tiny oil jar. “None of those men are bitter enough to cause trouble, not after making lives with the women and girls of my tribe, the mothers whose daughters you saved at Bibracte.”

He offers the oil up for Skipio, who sniffs it before shaking his head with a furrowed brow. Welle grabs another, this one in a glass ampule, and places its little topper under the Roman’s nose. Verdant eyes approve with a rising chin.

Welle dabs the pungent cologne across Skipio’s neck and behind his ears before the man raises his arms for more. “You’re taking a blade to your pits.”

“Britannia was the most humid place in the world,” Skipio says. “I got into the habit of shaving everything while there. Everything.”

Welle clears his throat, training his eyes anywhere but Skipio’s groin. The man pulls on the black, long-sleeved tunic and, keen to make the ensemble work, Welle digs through the wardrobe until he finds a green-corded belt. He ties it around Skipio’s waist before rummaging through the cabinet’s lowest drawer for a ball of black socks.

“Welletrix,” the Roman stands over him. “May I have my medal back?”

Welle rises and faces him. “I wish to apologize for taking it.”

“No doubt my prisoner showed you where to find it.” Skipio holds out his hand. “The next time you need it, simply ask me.”

“The druid still has the others,” says Welle, taking the disk from his pocket and setting it within the man’s palm. “As for asking you, I wished to avoid involving you in our affairs.”

Verdant eyes soften. “Village affairs are my affairs.”

“I speak of tribal affairs, Lord Skipio.”

“I am not of your tribe,” he wonders. “But my prisoner is?”

“I know of your Gallic taint, but it was decid—”

“It was his idea, wasn’t it?” he interjects. “Sacrificing that man?”

Welle says, “That man was a child rapist and a coward.”

“I know what he did, I emasculated him for it.” Skipio opens the trunk. “I don’t feel there was any need to punish him further—”

“Punish him?” Welle balks. “He was given to the Dark Lord, an honor he didn’t deserve.”

Skipio tosses the medallion into the trunk. “I see.”

“If you must know,” Welle adds. “We approached the druid—”

“We?”

“Myself,” says Welle. “I appro—”

“I’m not seeking retribution.” Skipio smiles, his perfect teeth made chalky after a morning rinse of goat’s milk and cat urine. “If you wish to keep the tribal leader’s name to yourself, that’s fine.”

Welle follows the brawny man to the cushioned bench.

“All I ask,” Skipio adds, “Is that you tread lightly when it comes to the druid.”

“I’m no stranger to his bloodlust. I’ve dealt with men like him before.” Welle unfolds the sock ball and kneels before him when he sits. “I must say that the druid, unlike those I’ve known before him, keeps to his self-imposed boundaries.”

“Boundaries?” Skipio tuts. “That bitch is pure chaos.”

Welle slips a sock over the man’s toes. “No one’s denying that.”

“He has a talent for stoking all the wrong urges,” huffs Skipio. “Your tribe would do best steering clear of him.”

“We make our own choices, Lord Skipio.” Welle stands. “That being said, his role as our druid isn’t to inspire faith, but to amplify it.”

Skipio stares at the thin, icy skin on the wet porch. “Is that why you, who loathes human sacrifice, suddenly consigns yourself to it?”

“I’m no stranger to violence, Lord Skipio.” Welle seeks a hint of guilt in the man’s mossy eyes. “None of us is the same person we are in desperate times.”

“Desperate times?”

“Nature has been unkind to the villa these few past winters.”

“And here I am,” says Skipio. “Abandoning them before the first snow.”

“You needn’t worry about the village this season.” Welle picks tiny bits of wool from the man’s sleeve. “Lady Vita has always been there for the village. At least, she has since my arrival.”

Skipio regards him with a boy’s face. “Do you know anything about my sister’s strained relationship with Vitus?”

Welle begins dusting the bench cushion with last night’s tunic.

“Such truths aren’t mine to tell, Lord Skipio.”

“What truths?” he demands.

“Please ask no more of me on this matter,” Welle begs him. “Overheard conjecture in no way constitutes facts.”

“What in Jupiter’s cock happened while I was gone?” Skipio’s eyes find the ceiling and stay there. “Welle? Where did those holes come from?”

Hollow dents mark the white paint, and Welle knows precisely when the gangly druid slinked in and took the sharp point of a lance to the cloud cover; he just doesn’t know why. Before he relays this, Lady Vita’s laughter carries from the foyer.

“Planus is here,” says Skipio, noting Welle’s aversion. “Did you and Planus have a falling out?”

“Falling out implies that we previously shared space.” Welle folds his arms. “Such a circumstance never existed, Lord Skipio.”

The man blinks. “I thought he was your friend.”

“If I may speak plainly,” says Welle. “There’s been too many thoughts of late.”

“None of those thoughts are born from words spoken by Planus,” Skipio tells him. “He considers you a friend, Welletrix, and nothing more. And if I may speak plainly, there’s no better friend to have in this world than Gaius Planus Caesar.”

This is a truth that Welle knows better than anyone. The subject of Planus and their time together at Bibracte pesters him like a persistent hour fly. Whispers persist of a camp romance, and there might’ve been one had the handsome Roman taken the advantage.

The journey to Villa Servii from Bellagio takes an entire day if one departs before sunrise. Legatus Caesar arrives in time for a quick bath and a quicker meal before escorting Servius Tribune and his sister back to the Lario.

Welle follows Lord Skipio out, but rather than accompany him to the front impluvium, he ventures into the kitchen, where Niko prepares a hefty pigeon for their guest. He seasons it with rosemary and salt and will serve it on a bed of tender peas fried with prosciutto strips. He finds the mute cook’s ceramic frypan on the fire, ribbons of tender red sizzling amidst deep green pellets that gleam with olive oil. He sneaks no taste, preferring his sautés with butter.

Caeso and Optio idle in the kitchen, their habit when there’s a songbird on the spit. They wonder why the Caesarian Legate bothers to make a day’s journey into these mountains when he could easily meet Lord Skipio on the banks of the Lario.

Niko’s knowing eyes shift to Welle before a blink returns them to the frypan. Never one to suffer gossip, even when he isn’t the subject, Welle barks fresh commands, his voice cutting through the houseboys like a whip. The carpentum needs tending; secure the Lord and Lady’s travel trunks on its top and refit the iron rings around its wheels. Caught off guard by the blond Gaul’s sudden wrath, both scramble to escape as he adds more to the list, demanding they wipe down the leather seats and shake the dust from all four window curtains, not just the two in back!

Welle retires to his room, taking no pride in his plucked nerves.

He takes inventory of the space given to him in this house, two years of filling it with things from his previous life. What he couldn’t salvage, he replaced with reasonable facsimiles, like the fading brown floor rug with the same blue thread that ran through his grandfather’s linens. The leg of his mother’s narrow wardrobe flattens the rug’s stubborn right-corner curl. Made of naked birch, the cabinet lost its elk-bone handles, leaving two holes smaller than the black of his eyes.

That spring day, when Rome caught up with them at the river crossing, this piece of furniture was all mother could get onto the raft. A noble Helvetii, she packed up their household to join the eastern migration, after her husband, a Veragrii fur merchant that Welle called father, died of coughing sickness.

His death kept Welle under his mother’s roof, and it didn’t take his blood father, a wealthy man named Orgetorix, long to sniff him out among the migrating families. His blood father offered a better life in return for serving him, but Welle refused to leave his mother and toddling sister.

Welle’s grandfather had been an important leader, whose name carried weight among the southern tribes, particularly the ageing King Divico. That’s why Orgetorix wanted Welle around, to convince Divico to call upon the governor, Kaiser, and seek his permission to migrate through Roman lands.

A shrewd man, his Roman name, Caesar, refused.

Before leaving that night, Welle visited this governor, who graciously served him a meal. That’s where Welle first saw Gaius Planus, the son of the host’s cousin. Welle ate nothing, nor did he drink, pleading only for his tribe to be allowed passage. That’s when Caesar revealed that Orgetorix wasn’t leading the Helvetii to a better life, but giving them to the Aedui and Sequi to serve their armies in uniting against the Roman Republic.

Welle’s digestion of this truth led to mistakes, the first of which proved most damaging. He confided in his half-brother about speaking with Caesar, about how their father was instigating an altercation with Rome that none of them would survive.

Welle had underestimated his half-brother’s ambition and knew nothing of his savagery until it was too late.

King Divico kept the migration going, but Rome caught up with them all on the banks of the Saône. The women and children crossed first, with Welle putting his mother and her toddling daughter on one of the larger rafts. She took only her birch wardrobe, ordering Welle to abandon the rest. Navigators strung thick guiding ropes between the banks, pulling on them to move the flat vessels across.

Fear brought out the worst when the first Roman horses appeared on the hill. Wealthier families commandeered the rafts, loading them with carriages, livestock, and servants.

Welle had brandished a sword and loaded a raft with a group of elderly men, angering his half-brother. Rome arrived before their words turned to blows. Swordsmen on horseback and spear-chuckers began decimating the most vulnerable.

Despite his protests, the old men pulled Welle onto their raft. He grabbed the rope and joined them in ferrying it across. Onshore, his spiteful half-brother cut the guide rope, forcing their raft to drift with the current under a rain of Roman arrows. He and the men hid under the first to die. Water rushed under one ear while blood dripped from above into the other. The raft made landfall some miles downriver.

Planus Caesar led his men to the bank, their arms holding long, narrow boats. Cut logs arrived by way of horse carts, and the engineers tied together rafts, fixing them atop the skinny boats to form a floating bridge. The legion’s numbers were so great that it took them a whole day to cross it.

Welle fled with the others, and Rome followed, never attacking with weapons, not when their looming presence took a greater toll. Always within eyesight but many miles behind, uncertainty and fear led mothers to smother their babies and poison themselves.

Rome eventually chose violence at Bibracte.

Welle hastily wipes away the tear from his cheek.

His first week as a prisoner found him hiding from his half-brother among the Tulingi and Boii, sent by their dead masters to aid the migration. Every morning, Gaius Planus jogged past the prisoner yard with his engineers, their calisthenic routine taken before sunrise. One day, Welle caught the centurion staring at him longer than most, so he made a life-saving decision to approach the man.

Welletrix the Veragros, bastard son of Ogretrix, offered his body to a Roman to escape his vile half-brother, Marcus Clausius Oppelius.

No love affair came from revealing his identity, as Planus proved an honorable man whose only demands were playing endless rounds of Five Lines and long nights filled with talk of places never seen.

A deep breath and a steady sigh calms his tension—until he realizes someone’s beside him. Welle turns to find the chubby Niko holding a tray. Upon it sits a crock, a dull paddle-blade, and a small, steaming rye loaf. He sets it on the table beside Welle and removes the tiny crock’s lid to reveal a dark yellow paste.

Unable to stop himself, Welle pokes a finger into it, bringing a dallop to his mouth and savoring its rich, salty sweetness.

“Did you churn this for me?” he asks.

Niko’s hands retreat under his apron.

“The color is beautiful. It’s milk from the Po grasslands, isn’t it?” Welle tears into the bread and then paddles some butter onto it. “It’s so perfectly salted. Did you add the salt while churn-?”

Niko is gone, and his door is closed.

Welle devours the little loaf, relishing every warm and buttery bite. Wind blows from the high window near his bedding loft, whipping the threadbare drapes against the ceiling. He must thank Planus for the milk and then repay Niko for his kindness.

Then, something strikes the wall he shares with the druid. A tiny dust cloud enters his space as a bit of plaster strikes the floor. Lord Skipio cries out in pain, followed by a joyous guffaw. Thumping follows as the druid bounds up his staircase, and moments later, a thud as his rangy feet land on the hortus rocks outside.

Welle leans back in his chair and rests his feet on a step of his staircase. He finishes his buttered bread with plans to visit Planus before he departs. Lord Skipio’s leathery boots speedily tap past his door and toward the front porch. He’ll chase the little cretin into the trees, they’ll knock each other around until the druid tires of it, and then Lord Skipio will breed him and be back in time to board his carriage with Lady Vita for their trip to Comum…